- Become a member of the New England Wild Flower Society. (If for no other reason then because it’s free admission for you and your kids or guest at Garden in the Woods.)

- The Society puts out a magazine, Native Plant News. It’s good – one of the few magazines I usually read cover-to-cover.

An excerpt from Elizabeth Farnsworth’s essay, Is “New Conservation” Still Conservation?, in the Fall/Winter 2014 issue of Native Plant News:

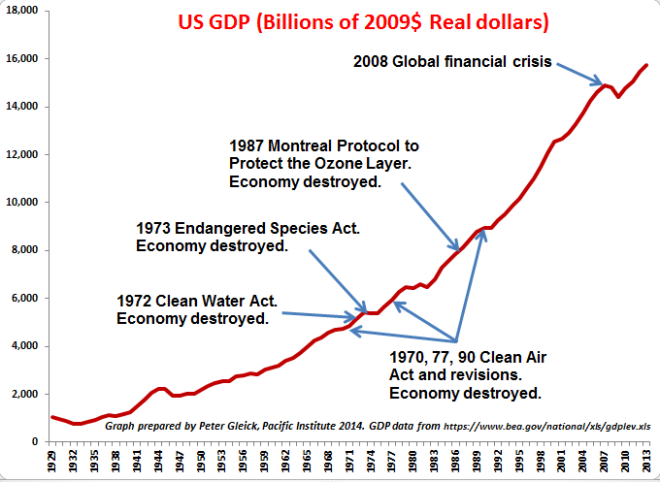

Adherents of “New Conservation,” which is also called Environmental Modernism, understand that simply creating ecological preserves is not sufficient to protect biodiversity on this planet. Proponents acknowledge that with a global population exceeding seven billion people, humans have altered and continue to affect, in some way, almost every location on the globe. They recognize that humans have a need for natural resources. But they also see the natural world as highly resilient, able to withstand all manner of alterations and extinctions. therefore, they pursue conservation strategies that establish partnerships with large corporations and sanction natural resource extraction. Although this seems on the face of it like a reasonable position, New Conservation has stirred considerable controversy among the field’s leading conservation biologists. touched off in 2012 by an article authored by Peter Kareiva (chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy) and colleagues, titled “Conservation in the Anthropocene: Beyond Solitude and Fragility,” a lively debate continues to rage in the scientific and popular literature. [Ed.: Link added.]

New Conservation erects a straw man by portraying conservation scientists as naïvely focusing on protecting “pristine” wilderness and ignoring the need to work with many stakeholders to demonstrate the economic value of conservation. Adherents of this doctrine quote selectively from early texts by Thoreau, Emerson, Hawthorn, Carson, Muir, and Abbey that plaintively decry the destruction of wilderness, and then claim that we continue to cling to unrealistic, idealistic concepts of nature. But although those eloquent writings spurred the nascent environmental movement, they are no longer the primary arguments used by today’s conservationists to justify land and species protection. Conservation scientists on the ground grapple daily with the hard realpolitik of a burgeoning human population, political destabilization, and economic inequality, and struggle to balance human needs and limitations with the fundamental imperative to protect and sustain biodiversity and ecosystem function.

New Conservationists posit that current conservation strategies have failed at protecting biodiversity because they disregard two facts: 1) nature is highly resilient, not fragile; and 2) appealing to human interests is central to ensuring enduring land and species protection. in fact, these ideas are not new. Conservation organizations have long realized both that humans are an essential part of nature and the conservation equation, and that, given world enough and time to recover from anthropogenic stress (and with some help from restoration efforts), degraded landscapes can provide functional habitats and supply important ecosystem services to humans and other organisms….

Continue reading →