Category Archives: Economics

Mint the Coin

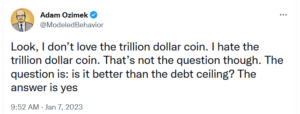

The House is controlled by a bunch of sociopaths who want to burn everything to the ground. We’re going to run up against the debt ceiling again in 2023. As it approaches, they’re going to use the threat of default to try to extort all kinds BS. The best suggestion for neutralizing the threat I’ve heard so far: Mint the Coin. The headline nails it, “The debt ceiling is an absurd problem. Only an absurd solution can save us.”

Student Loan Foregiveness

So tonight I log on for the first time in god knows how long and I see an draft of a post I started to write in 2020. I haven’t touched it since – still just a brain dump and excerpts of pieces other people wrote – but interesting that I still see things pretty much the same way as I did then. Anyhow, here’s the unedited draft –

A few questions to frame the discussion of student debt forgiveness:

- Why privilege forgiveness of student debt over forgiveness of other types of debt, e.g., medical debt?

- What’s the root cause of the student debt crisis? What, if anything, will debt forgiveness do to address the root cause?

- What broader social goods will be achieved by forgiving student debt?

I remain lukewarm about straight-up debt forgiveness because I don’t have satisfying answers to those questions and I haven’t heard any from anyone else. Continue reading

Thought for the Day – October 10, 2020

Degrowth: A planned reduction of excess energy and resource use in rich nations to bring the economy back into balance with the living world, while reducing inequality and improving people’s access to the resources they need to live long, healthy, flourishing lives.

MA energy policy: Cutting CO2 emissions vs reducing electricity costs

I have some initial thoughts after initial reading of Paul Levy’s piece on solar in MA, “Has the Mass. solar gamble paid off? Like other energy bets, costs high, hidden.” Levy’s introductory paragraph:

How much should we pay to promote solar energy in Massachusetts? Recent state government programs have resulted in the commitment of at least $10 billion of consumer funds—well over $1,500 for every man, woman, and child in the state. Is there a need for more government-directed subsidization, or have we reached a point of diminishing returns? Let’s look at the big picture.

and his conclusion:

What’s next on the list of well-intentioned financial mandates that will help reduce the risk for the developers of new energy technologies by passing along costs to the rest of us? Rest assured, the government will be asked to gamble with our money. And investors and advocates will do their best to keep things hidden so the rest of us don’t understand the costs they are asking us to bear. Some advocates now want unwarranted energy storage incentives. Some even argue for a return to expanded solar incentives. Let’s keep an eye on things and demand cost-effectiveness and transparency with regard to the amounts promised on our behalf.

There’s a lot in between. Unfortunately, he missed the big picture. The purpose of the “solar gamble” is to help transition us to using carbon-free (or at least carbon-neutral) energy not to save consumers money. The latter is a fringe benefit not the primary motivation. Levy misses the big picture because his focus is on financials. Money matters and how the costs of transition are shared – that they’re shared equitably – is important but leading with financials sets the wrong tone.

Thought for the Day – July 28, 2018

It’s especially important to press these priorities of security and solidarity now, when the share of US GDP going to profit has increased since 1984 from 2% to 16%–a difference totaling $17,000 per US worker. Wealth is jointly produced; well-being should be jointly achieved. https://t.co/eWSDDIMKs0

— Jedediah Purdy (@JedediahSPurdy) July 27, 2018

Power your house with your electric vehicle

Interesting article PV Magazine, California electric car culture to cheaply cook the duck curve:

Researchers at the US Department of Energy (DOE) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) have done the math on California’s 1.5 million zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate and found that the cars’ batteries can meet the goals of the state’s 1.3 GW energy storage mandates by absorbing a healthy amount of daytime overproduction and mitigating the early evening duck curve ramp.

Learn more about the duck curve here.

To make it work, it’ll mostly take controllable one-way car charging from the grid (V1G) and a small amount of two way charging/discharging from the car and the grid (V2G) to be used on the worst day of each forecast year.

That’s right, use your EV as a battery to power your house after you get home in the evening. Continue reading

Russ Roberts, “The Human Side of Trade”

11. Roberts writes: “Having only 2% on the farm [down from 40%] is a feature, not a bug. It’s a good thing. It’s a glorious thing. Because it allowed the creation of all the glorious things that would amaze the farmer brought into the present — the smart phones and the artificial knees and youtube videos, and cross-country travel and cars and the longer life expectancy and everything else we didn’t have in 1900 that makes life more pleasant and even more meaningful for the children and grandchildren of farmers in 1900.”

YouTube videos make life more meaningful?… Fine, I won’t argue that. Of that 38% who moved from farm to other occupations though, how many are involved with building artificial knees? More generally, what became of them? What fraction took manufacturing jobs, the kind that have been disappearing over the past few decades.

12. Also, with respect to migration from the farm and other demographic changes since 1900, I think of Robert Gordon’s paper from a few years back, Is U.S. Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds

13. Roberts writes: “Fracking - lower prices coming from innovation – is potentially more reliable than cheap imported energy that could go away. But that difference doesn’t change the point that the full benefits when prices fall from either change has a wider set of effects than just less expensive energy.”

Environmental impacts of continued reliance on carbon-based energy – you might want to look into those, Russ.

Thought for the Day – August 17, 2017

This 40 year old commentary aged well:

Sometimes I think we were more eloquent 40, 50, 60 or more years ago.

This half-finished post from mid-2017 is a reaction to Russ Roberts’ commentary, The Human Side of Trade. Apologies for the listicle.

Roberts: “Suppose a scientist invents a pill that once you take it lets you live until 120 with no health issues whatsoever. Once you turn 120, you die a peaceful death on your birthday.”

Such a pill would fundamental change the nature of what it means to be human. Economics aside – and even if the economic impacts were all positive – the pill he describes strikes me as an awful invention.

Related reading: “Being Good Enough” by Bill McKibben – http://dark-mountain.net/blog/key-posts/dark-mountain-issue-8-techne-2/

I admit that I stopped reading Roberts’ piece after he introduced the magic pill scenario. But, trooper that I am I went back to it. Wow, it got even worse after where I left off. A few thoughts:

1. I have no more in common with Roberts than I do with people who believe that the Bible is literal truth. The man is not short on hubris.

2. A joke I heard 25+ years ago: President Gorbachev was visiting a farm one day and a peasant asked him a question, “Comrade Gorbachev, was Comrade Lenin an experimentalist or a theoretician?” Gorbachev pauses then replies to the effect of “Perhaps both.” The peasant responds definitively, “No. He was a theoretician. An experimentalist would have tested Communism on rats first.” Roberts is also a theoretician.

3. Reading pieces like Roberts’ gets me thinking that Christopher Lasch had it right.

4. Roberts writes: “In 1900 about 40% of the American work force was in agriculture. Now it’s about 2%… Having only 2% on the farm is a feature, not a bug. It’s a good thing. It’s a glorious thing.” That only 2% work in agriculture implies that 98% of the population have no concept of how to feed themselves if their lives depended upon it which, coincidentally, if there were a major disruption in the food chain it would. That does not strike me as a glorious thing.

5. One can have too much of a good thing. There is a tension between efficiency and resilience. Efficiency feels good and, so long as everything runs smoothly, it’s great. However be aware of the “The better your four-wheel drive the further you’ll be from civilization when you get stuck.” effect. If you ignore resilience in pursuit of efficiency then you set yourself up for a nasty failure.

6. Doctors, nurses, chemists, etc wouldn’t be put out of work immediately because people like myself would want nothing to do with that pill. We’d die off eventually but demand for people working in health-related professions wouldn’t immediately go to zero.

7. Is it important to deal with adversity in your life? Would the magic pill make us soft psychologically? If it did would it matter?

8. Take the pill and no health issues for 120 years but you’re dead on your 120th birthday? I suppose some people really like for their lives to be as deterministic as possible.

9. Roberts writes: “I once debated NAFTA on the south side of St Louis surrounded by autoworkers who were threatened by open trade with Mexico. A machinist, who happened to be the brother of the guy I was debating told me had already been out of work for years. “What are you going to do for me?” he asked. I didn’t tell him to find comfort from the fact that his children were going to lead better lives. I wasn’t sure what to tell him. So I asked him what he wanted. Did he want a check? He said “I want my job back.” He said he wanted his job back, but what I think he really wanted back was his pride and dignity.”

How do children of the long-term unemployed fare relative to those whose parents have steady work? I’m guessing that the stress of parents worrying about how they’re going to pay the mortgage or rent or buy food doesn’t have a positive effect on their kids. Just sayin’…

Maybe that machinist really did want his job back. The work may have been particularly satisfying to him. Maybe pride and dignity was it but don’t dismiss the particulars of the work itself.

10. I recommend Samuel Florman’s essay, Nice Work