I read two noteworthy posts last week on inequality in the US. One was by Thomas Edsall in the NY Times, What if We’re Looking at Inequality the Wrong Way?, and the other was Inequality and Mobility, Again by Jared Bernstein. Edsall’s piece first.

Edsall’s column was on a paper by Cornell professor and American Enterprise Institute adjunct scholar Richard Burkhauser, “Levels and Trends in United States Income and Its Distribution“. Burkhauser and co’s (hereafter BLA) assertion is that those on the bottom end of the income scale have actually done better in relative terms over the past few decades than those at the top. They claim that assertions to the contrary are based on a failure to look at the whole picture in terms of income, benefits, and increases in net wealth. Edsall:

Richard Burkhauser and his allies [Jeff Larrimore and Philip Armour] have … a new paper, “Levels and Trends in United States Income and Its Distribution,” which was published earlier this month. In the 2013 paper, Burkhauser [et al. have] come up with statistical findings that not only wipe out inequality trends altogether but also purport to show that over the past 18 years, the poor and middle classes have done better, on a percentage basis, than the rich…

Burkhauser et al. achieve their reversal of past income distribution data by amending the definition of income developed in their 2012 paper — “post-tax, post-transfer, size-adjusted household income including the ex-ante value of in-kind health insurance benefits” — to incorporate another accounting tool: “yearly-accrued capital gains to measure yearly changes in wealth.”

Although “yearly-accrued capital gains” sounds innocuous, it is a game changer.

Burkhauser attempts to measure the year-to-year increase in taxpayers’ assets — stocks and bonds, housing and privately held businesses – and to count those annual increases as income. Increases in the value of such assets do not show up in tax data because they are taxed by the federal government only when the asset in question is sold and the increased value is realized as taxable gains.

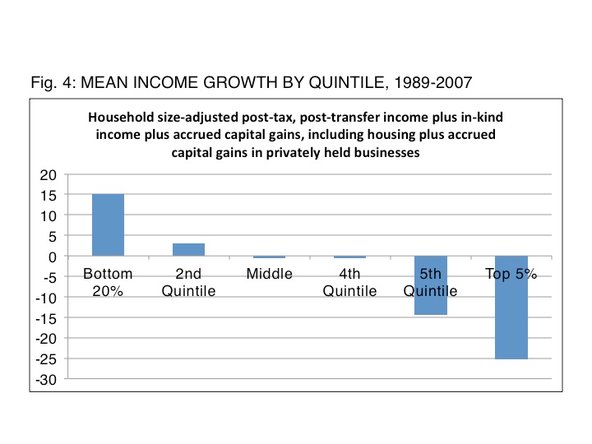

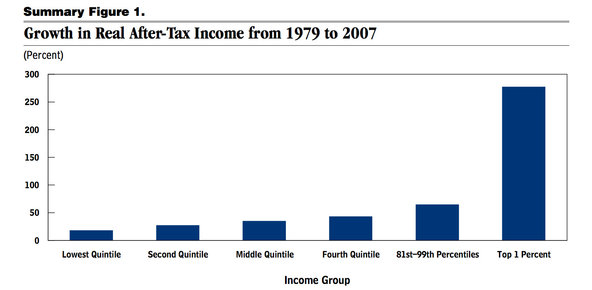

In a nutshell, BLA claim that the reality is

not this

Methodology matters. Edsall quotes Dean Baker pointing out an obvious flaw in BLA’s method for computing income:

If they want to make a big point of saying that middle and low income people would not have been harmed by inequality over the years 1989-2007 if they could have all sold their homes at peak bubble prices, they are welcome to do so, but that seems more than a bit silly to me. We know what this measure would look like today with the real value of homes down by around 30 percent and homeownership rates in the bottom two quintiles down by around 10-15 percent. Are we supposed to ignore that fact?

To appropriate a phrase I heard a last month on a different subject, BLA “is not just comparing apples to oranges, they’re comparing apples to oranges you can’t even buy.”

Edsall’s concluding paragraph sums up the problem with BLA nicely:

A key purpose in measuring both wealth and income is to determine what kind of standard of living is possible for those at the top, the middle and the bottom. Do individuals, families and households have enough to provide for themselves, perhaps most importantly for their children? Do they have the financial resources to enter the highly competitive global marketplace?

On that score, Burkhauser’s use of “yearly accrued capital gains” fails the test of measuring what is most significant to know in policy making and in assessing the true quality of life in America.

[UPDATE 6/30/2013: Jared Bernstein weighs in on BLA here.]

[UPDATE 7/1/2013: Dean Baker had a post last week documenting the shortcomings of BLA – see here.]

That was one of the noteworthy posts. The other was was Inequality and Mobility, Again by Jared Bernstein. Here are a few excerpts provided to try to entice you to go read it:

There are at least three arguments why our historically high levels of inequality are far from benign:

–they reduce access to opportunities and thus reduce economic mobility;

–they lead to slower macro-economic growth;

–they violate basic fairness as those who are growing the size of the pie end up with smaller slices.I have a long paper on the second concern coming out soon. The third point is especially compelling to those who focus on the fact that median income or earnings used to track productivity growth up until around three decades ago.

But the first concern is one I raised well before we had any data for it …

The economist Miles Corak has an excellent new article forthcoming that collects what’s known about the relationship between inequality, opportunity, and mobility… While [Harvard economist Greg] Mankiw sees little evidence that inequality has reduced opportunities, Corak comes to a far different conclusion:

Inequality lowers mobility because it shapes opportunity. It heightens the income consequences of innate differences between individuals; it also changes opportunities, incentives, and institutions that form, develop, and transmit characteristics and skills valued in the labor market; and it shifts the balance of power so that some groups are in a position to structure policies or otherwise support their children’s achievement independent of talent.

… for years, I and others would hold up pictures of worsening inequality and explain the causes as best we could and pretty much leave it at that. We were operating largely from concern #3 above—fairness. I got into this in the 1980s when economists were first connecting inequality to sticky poverty rates (why weren’t poverty rates falling as the economy was growing?).

I still consider this an important and valid concern but over the years, I’ve come to see the consequences of our inequality problem as running deeper, striking at opportunity and mobility in a manner that should cause grave concern among anyone who’s paying attention, regardless of their political stripes. There is nothing benign about it.

Related: See David Cay Johnston’s reporting on falling wages.

Also related: Noah Smith with a 21st century fable for working people, “I get what you get in ten years, in two days.”